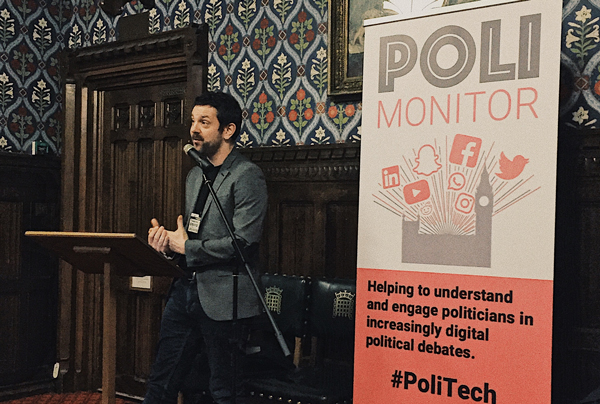

On 5 March 2019, I was invited to speak at the Palace of Westminster in London at the ‘Social media and politics: spreading fake news or strengthening democracy?‘ event organised by PoliMonitor. The following is the script for my remarks, an update of sorts to the argument I put forward in Social Media and Everyday Politics and the follow-up writing:

In this current moment, a time of Trump and Brexit and Cambridge Analytica and AI and surveillance and algorithmic governance and data capitalism, there’s a lot we can talk about when we consider the opportunities and – especially – the pitfalls and social media and politics. The discussions we’re having though are not new – they are just taking on new significance, responding to new opportunities and developments, given the power and possibilities of major social media platforms.

I’ve been researching various intersections of the digital and the political, the social and the everyday for over a decade. The specific topics and sites of my research have changed over that period – I started with blogs and citizen journalism projects in France in the aftermath of student protests against a proposed youth employment law, and currently I look at the political implications, opportunities, and challenges of visual social media, from Instagram Stories to selfies to GIFs to emoji. Along the way, I’ve carried out a lot of studies of Twitter and hashtagged politics, and a few years ago published a book on Social Media and Everyday Politics.

What’s been clear throughout all my research is that when we talk about social media and politics, it’s not an either/or of spreading fake news or strengthening democracy… It’s both, and it’s neither, and it’s everything at once. There are positives, negatives, opportunities, limitations, and far more aspects which complicate the situation. Regardless of the platform, people use social media to talk about politics, to engage with issues, to comment about major events in the same ways that they do so to stay in contact with their friends and family; and because these are spaces that people are active on, there is an interest for political actors, established media, advertisers, and more to also find a way to make use of these platforms.

People will find ways to be political using digital technologies, whether explicitly or tangentially, and this works across the political spectrum. We can talk about the prominent examples, the success stories – for whatever value of success you want to use here – about the digital in the Arab Spring, or the Occupy movement, or Black Lives Matter or #MeToo. We can talk about the opportunity they provide for marginalised and underrepresented voices, from LGBTQ communities to indigenous perspectives in Australia … and we can talk about the digital strategies of the alt right, of Gamergate and Mens Rights Activists. And we can talk about complicated political viewpoints and issues which can’t be easily distilled to a single hashtag. It’s the same platforms being used, people of different views making use of what is possible on them. These are not social media-only concerns, and success is not purely determined by whether or not social media are being used. But understanding how social media are used, and why, is important here.

The everyday practices of being on social media become politicised, since it’s the everyday that informs how to engage with, to communicate, to comment on what else is happening. Something as seemingly fleeetjng or frivolous as Taking a selfie is not necessarily political, but if it’s taken in a polling station, or to make a statement against prevailing sexist, racist, or otherwise oppressive attitudes, then this everyday form of social media activity becomes a political act.

The digital, in its various forms, also affords opportunities for engaging with the political process that were unexpected, not part of the design of platforms or what they were intended for. The political dimensions of emoji, for instance, come from what they represent – and who they don’t represent – as well as the meanings that get applied to them by everyday users, using pictograms to stand in for feelings or denote membership of an ideology, among other things. These are not things that were necessarily thought about by the designers of the emoji or the consortium which reviews and approves new emoji – and this is one of the key advantages and challenges of social media in general – emergent practices and cultures will develop in unexpected ways, working with and around what is possible on a platform.

What I want to highlight here, then, is that while social media are used to be political, what examples of the Cambridge Analytica scandal have also underlined is that how digital media are implicated in the political— from user practices to platform policies and how they are enforced, in support of and against whom — is a critical question. As my research examines, political (and politicised) practices develop among social media users and communities, beyond the aims or intended functions of the platform developers, but the platforms and their owners and stakeholders have their own politics that until recently were often overlooked by the political opportunities that emerge out of user activity on Twitter or Facebook; and indeed, for the platforms themselves, the success stories are promoted to demonstrate their own public worthiness, their social contribution, their apparent neutrality, despite what they have also been doing behind the scenes. The politics of social media is ever more important to consider here; the competing opportunities of being political on, and with, social media, vs. the aims, the incentives, the partnerships of the platforms themselves…

The politics of an individual platform may be tangential, brought about or implied by particular affordances, or by rivals being more morally questionable. At a time when the everyday is increasingly politicised, social media and their everyday politics offer something incredibly important; they are heavily entwined in reflecting, representing, and reacting to what is happening. What is becoming increasingly critical, though, is reconciling what is the politics being supported, promoted, or amplified through social media, and what is the politics of the social media platforms themselves.